A Pole in an American corporation, By Witold Gadomski, Gazeta Wyborcza; June 27th, 2011

(this is an English translation of an article –http://wyborcza.biz/biznes/1,101716,9847219,Polak_w_amerykanskiej_korporacji.html?as=2&startsz=x )

20 Years In General Electric

At my age, it’s not about earnings, but about having fun. About being able to talk to the president of Deutsche Bank and ask him for his opinion on the crisis. Or to go to China or India and learn at the source where their economic success comes from.

“Somebody from GE spotted me during my scholarship in the US in 1991. They called me and offered a job,” recalls Lesław Kuzaj, 59, GE Regional Executive for Central Europe, associated with the corporation for almost 20 years. “But I politely refused. I was engaged in real business, we wanted even to launch an airline and compete with LOT. I thought in a corporation I would be only one of many small cogs in the machine.”

Since the late 1980s, Kuzaj was active in the Krakow Industrial Society. He had his own company, at the beginning a retail shop. He often cooperated with Americans: in 1988, he established the Krakow Banking Society which later was transformed into a bank, Pierwszy Polsko-Amerykański Bank KTB. With help of an American foundation, he established a business school. Also, he established a company with Polish and American capital.

In 1992, GE repeated its job offer. That time, Kuzaj did not refuse. He was invited to a series of interviews, from morning till night. They were looking for someone to build GE in Poland from scratch. His task was to find in Poland projects suitable for financing.

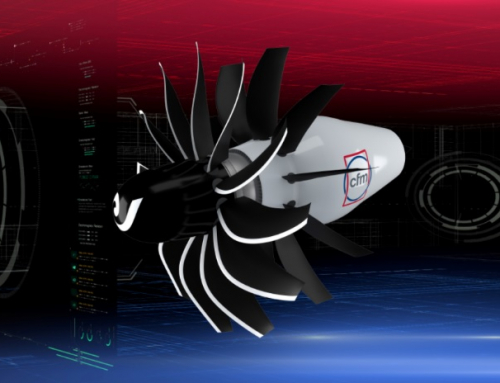

“After a few days, I was terrified,” says Kuzaj. “On hearing the news that GE had opened its office in the Intraco tower in Warsaw, many people started to approach me. Somebody asked about aircraft engines, somebody else about medical equipment, yet another about machine tools. I took the thick company catalog and saw how wide was the area of our operations.”

GE is one of only few American corporations to survive the whole 20th century. It was established in 1892 through a merger of Edison Electric Light Company, managed by Thomas Edison, and Thomson-Houston Company. From its beginning, GE was committed to innovations, first in the area of generation and application of electricity, but later the lines of business became more and more diversified.

In the 1980s, Jack Welch started a revolution in GE. “If you don’t have a competitive advantage, don’t compete,” the famous manager used to say. He started a large restructuring process. Welch understood that his corporation had the competitive advantage in the state-of-the-art technologies, but was unable to compete in household appliances which then were produced cheaper by Japanese (and presently by Chinese).

GE was also a weapon manufacturer. Welch decided that as the cold war was over, the company should get rid of that line of business. He sold the aircraft business to Martin Marietta (presently Lockheed Martin) and retained only the engine manufacturing business.

Kuzaj joined GE during Jack Welch’s revolution and learned fast about the restructuring and global business vision.

“My main problem was how to make the company interested in Poland. What unique advantages did we have in early 1990s? My idea was that we could be a sub-supplier of devices. I prepared a report on what products could be purchased by GE in Poland and which Polish companies could manufacture them. There were companies with competencies, design departments, but sometimes lacking a specific machine. Often, there were armaments companies with significant capabilities, but with no marketing. By the way, this is a problem of many Polish companies also today.”

The GE headquarters appreciated the report. Polish companies had a huge advantage in terms of costs. Kuzaj drafted in a few dozen high-ranked corporate managers. Then there was an “outsourcing fair” — a series of meetings between Polish companies and representatives of GE factories. The turnover was quickly increasing: from USD 5 million to 20 million and to 100 million. GE purchased the whole low-voltage business from Elektrim, with two factories in Bielsko-Biała and Łódź, and built the third factory in Kłodzko.

Following the impetus, Kuzaj proposed to establish the Engineering Design Center in Warsaw. At the begin, the Center recruited 20 engineers, young graduates from the Warsaw and Rzeszów Universities of Technology. Their tasks were to design small engine parts. Presently, the Center employs 1,300 people. They closely collaborate with the USA. They design subassemblies for state-of-the-art GEnx engines.

In 1995, following Kuzaj’s recommendation, GE acquired Solidarność Chase DT Bank. The Bank was established four years earlier by David Chase, an American of Polish origin (obviously, he had no connection with Salmon P. Chase, Secretary of Treasury in President Lincoln’s administration, who gave his name to Chase Bank, one of the American national banks). Solidarność Chase DT Bank was managed unprofessionally and probably would go bankrupt had it not been acquired by a stronger entity. Kuzaj was a member of the management board and then of the supervisory board of the bank. GE Money Bank quickly became a leader in consumer loans and installment plans. It had a huge advantage of being financed by the corporation. The invested dollars were used to give loans in Polish zloty, with multiplied profits. The loan boom in Poland was only emerging then. One time an extraordinary meeting of the supervisory board to increase the capital was called on a New Year’s Eve. The step was forced by the customers who stood in queues to get a loan. Two years ago, GE acquired BPH (the part not merged with Pekao SA).

Kuzaj’s successes were recognized by the headquarters. He was assigned to the Czech branch of the company. GE purchased there Agrobanka, a nearly bankrupt agricultural bank, then transformed to GE Money Bank (Czech branch). Then Kuzaj’s competencies were extended to Slovakia, Hungary, and Lithuania and in 2002 he became Regional Director, Central Europe.

“Any failures?,” I asked.

“Well, there were some during the 20 years,” Kuzaj answers evasively. “But perhaps they were not big, as GE has been putting up with me for so long,” he adds with a smile.

According to an anecdote circulating among the GE staff, whenever a new boss is appointed, his predecessor gives him this advice: “Destroy this company”.

The reality is not much different. On September 7, 2001, Jeffrey R. Immelt became the new corporate CEO. Four days later, he awoke in a different reality, similarly as whole America and the whole world. He knew that the existing business model would not fit that new reality.

“What will be the most important thing in the world after 9/11?,” corporate managers were pondering. “Of course, security”. And that is how the GE Security business was created, engaged in manufacturing passenger security equipment for airports, among other things.

Another recognized global challenge was water. GE Water develops water recycling systems, among other things.

The third recognized priority was the ageing society and demand for medical equipment. The corporation makes huge investments in fundamental research in the area of Alzheimer disease diagnosis and treatment.

GE is also active in the financial sector. Before the global crisis, it constituted a half of the corporate revenues. They emerged from the crisis a little battered, but still in a better condition than the competitors. They reported a profit even in 2009, the worst year for banks.

The crisis was another turning point for the corporation. GE gradually reduces its capital operations. Also, it has got rid of the media sector (until the last year, it owned CNBC, the world-largest TV news network specializing in economic matters, and NBC Universal, a producer of movies, among other things).

“Immelt said he didn’t want to check the audience ratings every morning with his heart in his mouth and he sold that business,” says Kuzaj.

The target for GE is to achieve 30% of revenues from financial operations and 70% from infrastructure in a broad sense, including healthcare, power industry, environment protection, water treatment, etc. Kuzaj gets excited speaking about modern, “smart” houses and whole cities controlled by GE equipment. Those are new marketing strategies tested in the departments of the corporation.

“Don’t you feel like a small cog in the machine?, I ask.

“One advantage of a corporation over a small company is that here I have virtually unlimited access to the necessary information and knowledge. From time to time we have meetings during which we talk about the world. We invite people who have the most interesting things to say at the moment. It would not be possible in a medium-size company. Another thing, GE employs now 10 thousand people in Poland alone. This is my greatest satisfaction.”

“Do you separate your private life from the job?,” I ask.

“As every manager, I had to learn that,” he says. “My favorite way of spending a holiday is to stay at home with my wife and two children. For one who spends hundreds of hours a year in airplanes and has visited GE facilities all over the world, a holiday in an exotic country is no attraction at all. I prefer to read books: now I read Wikinomics and Big Sur by Jack Kerouac. My musical preferences are typical for my generation: old-time bluesmen, Blood Sweat & Tears, Miles Davis, Weather Report. I also listen to jazz, Chopin, and Ravel. Earlier, my hobby was driving race cars. But if you are near sixty, extreme sports should be left aside. Bridge is what remains.”

“And what is your motivation?,” I ask. “Earnings, bonuses?”

“Not at all! At my age and with my position, it’s not about earnings, but about having fun. About being able to talk to the president of Deutsche Bank and ask him for his opinion on the crisis. Or to go to China or India, talk to the local managers and businessmen, and learn at the source where their economic success comes from.”

[FRAME]

From “Solidarity” to business

Lesław Kuzaj is a typical representative of the “Solidarity generation”. A degree from the Krakow Academy of Economics was not a ticket to a big career then, in the decline of Gierek’s communist regime. After the graduation, he became an administrative manager in the STU Theater and then a specialist in the foreign cooperation division of the Jagiellonian University. And then was “Solidarity”. Without that, his life would be completely different.

In September 1980, he became a member of the trade union committee at the University, then vice-president of the Małopolski Region, and finally, a delegate to the “Solidarity” convention in Gdańsk.

During the martial law period, he was engaged in illegal activities and was earning his living from ad-hoc jobs. He organized an underground radio station, cooperated with illegal publishers, at times in hiding and at times in the prison (he was severely beaten by prison guards). Until 1986, he was arrested and interrogated dozens of times. A typical history of an underground Solidarity activist. But in 1986, the regime eased off.

In 1987, the Krakow Industrial Society was established. It was an extraordinary mix of Solidarity activists, intellectuals, and small entrepreneurs. Small, because larger entrepreneurs did not exist at that time yet. The Society was founded by Mirosław Dzielski, a philosopher and political activist, who believed that private entrepreneurship was the best way for communist Poland to become a free country. In 1981, Kuzaj made an interview with Dzielski for Universitas, a monthly he contributed to establish. Among the Society members, there were a number of people who later became well-known businessmen, for example Lech Jeziorny and Andrzej Barański, president and owner of the Krakow-based Herbewo company. But most of the members have not made business careers. For several years, the chairman of the Krakow Industrial Society is Tadeusz Syryjczyk, who was a minister in a few cabinets after 1989.

Kuzaj was an ideal member of the Society. He had his own company, at the beginning a retail shop. But, in contrast to many other members, he not only talked about business, but treated it seriously.

“When Balcerowicz’s plan [of fundamental transformation of the national economy] was put into effect, I was invited, as vice-chairman of the Society, to the Harvard Business School to talk about the changes taking place in Poland. “Frankly, I wasn’t sure what was going on in Poland then. I was afraid people might demonstrate on the streets,” he says.

He obtained a business scholarship from the US Information Agency. He visited many places throughout the US: the Silicon Valley, banks, small and medium-size companies. He knew a lot of theory and now had an opportunity to see how the theory was put into practice.

And it was during that scholarship when he was spotted by people from GE.