Polish economy has much to improve in terms of innovation. Not a single Polish company featured in the European Commission’s 2012 scoreboard of top 1500 global R&D investors – says Magdalena Nizik, Chairman of the Management Board in GE Company Polska, and Managing Director in Engineering Design Center.

Polish economy has much to improve in terms of innovation. Not a single Polish company featured in the European Commission’s 2012 scoreboard of top 1500 global R&D investors – says Magdalena Nizik, Chairman of the Management Board in GE Company Polska, and Managing Director in Engineering Design Center.

By: Dariusz Ciepiela, Poland: wnp.pl, 10th May 2013

How would you say Polish economy performs in the area of innovation?

I am compelled to say that Polish economy has much to improve, both in terms of the outcome of the innovative process and its structure, by which I mean supporting institutions and instruments, as well as economic environment, legislation and administration.

In GE, we apply the concept called pillars of innovation where we analyse innovative aspect of government regulations, R&D investment of foreign or domestic companies, and education and staff training. GE view is that under this analysis Poland is lagging behind Czech Republic or Hungary, countries comparable in terms of shared past. Each year, the European Commission publishes “EU Industrial R&D Investment Scoreboard” of the top 1500 global R&D investors. In 2012, it didn’t list a single Polish company. In 2011, it featured Comarch, and prior to that KGHM and BRE Bank.

Why is that so?

Polish enterprises fear risk, whereas many innovative projects are not clear winners, especially at the initial stage, when one develops entirely new concept, spending money on the idea that may never take off. In Poland, there is no social approval for trying and failing, so enterprises are often very conservative in this respect. In the end of the day Polish companies do not come up with their own innovations, settling rather for copying western solutions.

Germany is one sound example of innovative economy. The European Commission estimates that in 2012 Europe was home to top 300 R&D companies, most of which were based in Germany. It is not a mystery that German economy fares better than others. Germany controls priority industries, which – instead of reproducing ideas developed elsewhere – invest in innovative solutions, thus driving the economy.

Is there enough support for innovation in Poland?

Compared with other countries, Poland is not a big R&D spender. In recent years we have seen some improvement in this respect, but only thanks to the EU funding. Let us look at “Innovative Economy” Program, which is a scheme designed to support innovation. Poland turned to the World Bank to evaluate how the scheme worked in its first 5 years. The conclusion was that not all the supported projects had real innovative value. Submitted applications did not have to meet such criteria like innovative potential of the project, its estimated impact on the domestic economy, or whether it contributes to strategic areas of the economy.

Innovation is also suffering from wide dispersion of support schemes and institutions. Additionally, strategies and schemes are vary region-wise. Small and medium enterprises find it difficult to find solutions that would work for them, so they hardly ever win financing. And small and medium enterprises are the ones that are in need of such support, since in their case there is no headquarters to provide financial backing from abroad. For small and medium enterprises, innovation means – at best – implementation of solutions developed elsewhere. Large international corporations can afford consultants who will specifically focus on finding financing opportunities.

You touched on reproductive nature of what Polish businesses do. To what degree this is driven by their ownership structure? Many companies are part of international concerns that have R&D centres located elsewhere.

Ownership structure is important. Polish companies need support and capital injection. Good news is that Poland succeeded in attracting major foreign investment. But for the economy to develop properly those investments must be accordingly prioritised. Polish enterprises with foreign capital have plenty of factories, call centres, or accounting centres, but they offer not that many jobs for highly qualified professionals. The rest of the world speaks of the war for talent, as high quality jobs are pivotal for the economy. I mean, certainly, we also need to create jobs for workers in the factory, but this is not what really drives the economy. We should prioritise creation of high quality jobs for highly professional staff, as innovative solutions – technologies, products, and materials – are brainchildren of no one else but those very people. Investors would not find the recruitment process difficult, as Poland boasts a good human capital.

This would imply that Poland has decent education standards?

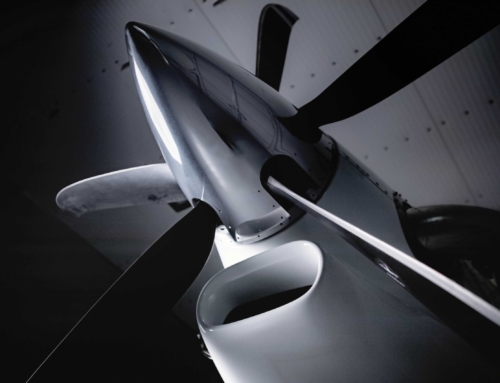

Poland has great technical university graduates, but they are too scarce in number. Educational offer is not that market-oriented as we could wish for, we are still failing to convince young people to go to technical universities, let alone secondary technical schools. I suppose we can even talk of crisis within the vocational education. Let me give you an example, here in Poland GE has a lab which designs new technologies and repairs complex structures, also for aviation and energy industry. We had real problems finding a welder. It appears there is a shortage of skilled workforce on the market.

Poland aspires to the role of a major player in aviation, we hear much talk about space technologies and this may surely result in interesting projects. But it is far from certain that Poland will become a global player in those areas. There are two global leaders of civil aviation industry and competing in these conditions may prove to be impossible and very costly. Let us focus on chosen innovative aviation technologies, leading the way in those more moderately defined areas.

Will Rzeszow Aviation Valley somehow boost innovation in aviation?

Polish Aviation Valley is a very valuable initiative that supports and streamlines cooperation of local manufacturers. Large factories of the region are owned by global aviation concerns that cooperate with small and medium Polish enterprises. This once more proves that one needs to view economic and innovative processes in global perspective. National industries are a thing of the past – the reality now is one global industry.

What kind of innovation support system do we need?

Certainly Poland is on the right path, although innovation policy could be applying more dynamic solutions. Poland transferred vast resources to R&D sector, although much of it was provided through EU funds. We need to increase our budget spending in this respect because there is a risk that once the EU funding sources are extinguished many innovative projects will be shelved regardless of their effectiveness.

There is also a need to reshape rules of the game for state-subsidized universities. We need to increase spending on technical universities, as well as secondary and post-secondary technical schools. With Polish economy as it is today, we have too many university graduates and not enough specialists. When someone wants to open, say, car repair shop, there are troubles finding the mechanic to do the job.

Increased spending on innovation is not enough. We must constantly monitor and adapt grant-awarding procedures to support really innovative projects instead of purely secondary activity like equipment purchase or overhaul of some ancient facility. Officials should adopt more open approach to innovative projects, and procedures should factor in the risk of failure, as it is part of the process. Currently, support schemes do not take it into account. GE invests billions of dollars in innovative projects knowing that certain percentage of that will perish. GE’s founder, Thomas Edison, repeatedly tried to invent the light bulb, before he actually succeeded.

Thank you for your time

Article from the http://logistyka.wnp.pl/polska-gospodarka-nie-jest-innowacyjna,197133_1_0_0.html